Mountain snowpacks provide an “extra” form of water storage across the Western US, acting as natural reservoirs that hold winter precipitation (as snow) from the cold wet season for release as snowmelt in the warm dry seasons when water demands for human and environmental uses, including irrigation, are high. The combination of water stored as snow and water stored in human-built reservoirs therefore is a useful indicator of developing droughts, persistent droughts, and the termination of

droughts in many water-supply systems of the western states. In a winter when reservoir storage is unusually low but snowpacks are unusually rich, it would be easy to imagine that a drought is occurring or soon to develop, if only the reservoir storage is reported. Conversely, in a winter when snowpack is lacking but reservoir storage is high (e.g., reflecting streamflows from a preceding wet year), it is easy to anticipate that a drought is coming, if only snowpack is considered. Remarkably, in most reservoir trackers, snow and reservoirs are reported separately.

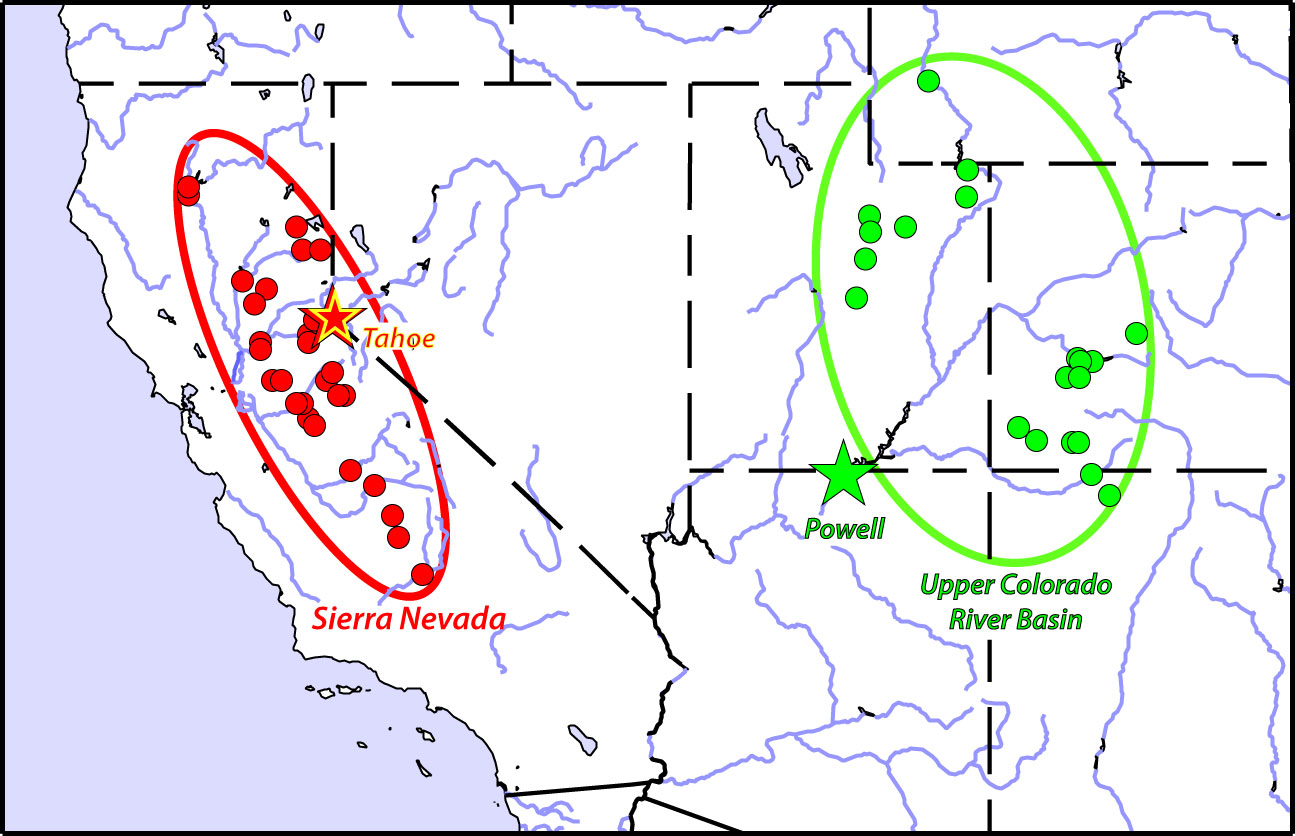

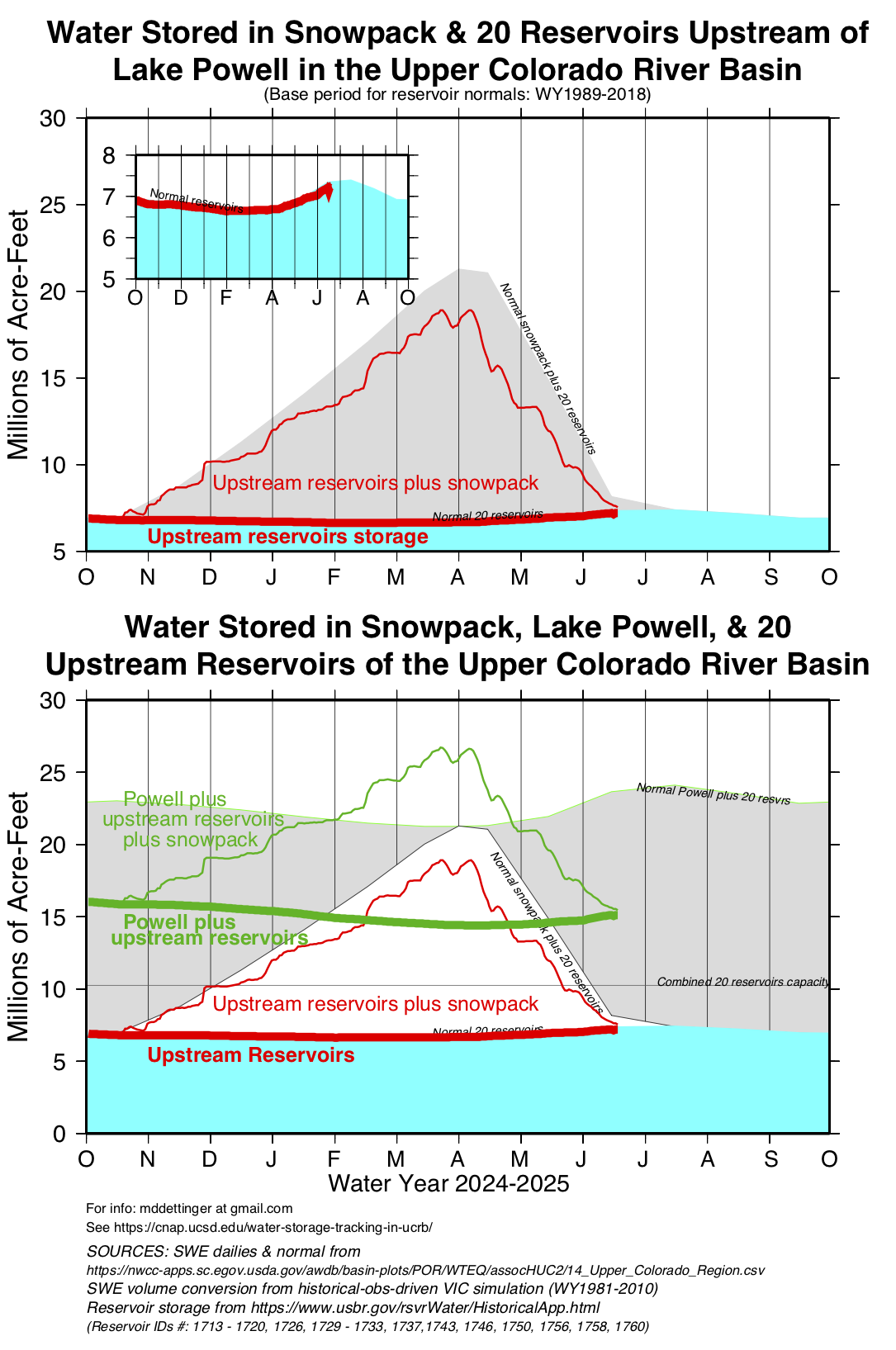

Below, we provide simple graphical summaries of the status of snow-plus-reservoir storage for the Upper Colorado River Basin (see map at right) to facilitate tracking of the overall storage in the combination of these two “reservoir” types, to allow quick judgements regarding the status of “storage drought” (Dettinger and Anderson, 2015; or

expanded version).

A similar set of graphics for the western Sierra Nevada of California–along with more discussion of this concept–is available

here.

UPPER COLORADO RIVER BASIN STORAGE (updated thru 06/19/2025)

A set of graphics showing the amount of water stored in 20 long-reporting reservoirs above Lake Powell in the Upper Colorado River Basin (UCRB), in snowpack above Lake Powell, and in Lake Powell, is presented below. Lake

Powell is one of two very large reservoirs–along with Lake Mead–that are used to manage the Colorado River for water users in all seven Southwestern states. Lake Powell storage is considerably greater than the total storage in the 20 reservoirs considered here, and is comparable to the long-term average yearly maximum volume of water stored in the snowpacks of the UCRB. Lake Powell is managed to provide reliable water supplies to many many water users (order of 20M) in the always dry but significantly populated Lower Colorado River Basin.

The upper panel of the UCRB graphic compares storage in UCRB reservoirs (above Powell) to long-term norms (inset graphic) and compares storage in UCRB snowpack-plus-reservoirs to their long-term norms. The lower panel compares UCRB reservoirs storage and UCRB snowpack-plus-reservoirs storage to UCRB reservoirs-plus-Lake Powell storage.

For comparison to developments this year, the corresponding graphics since water year 2016 are available here.

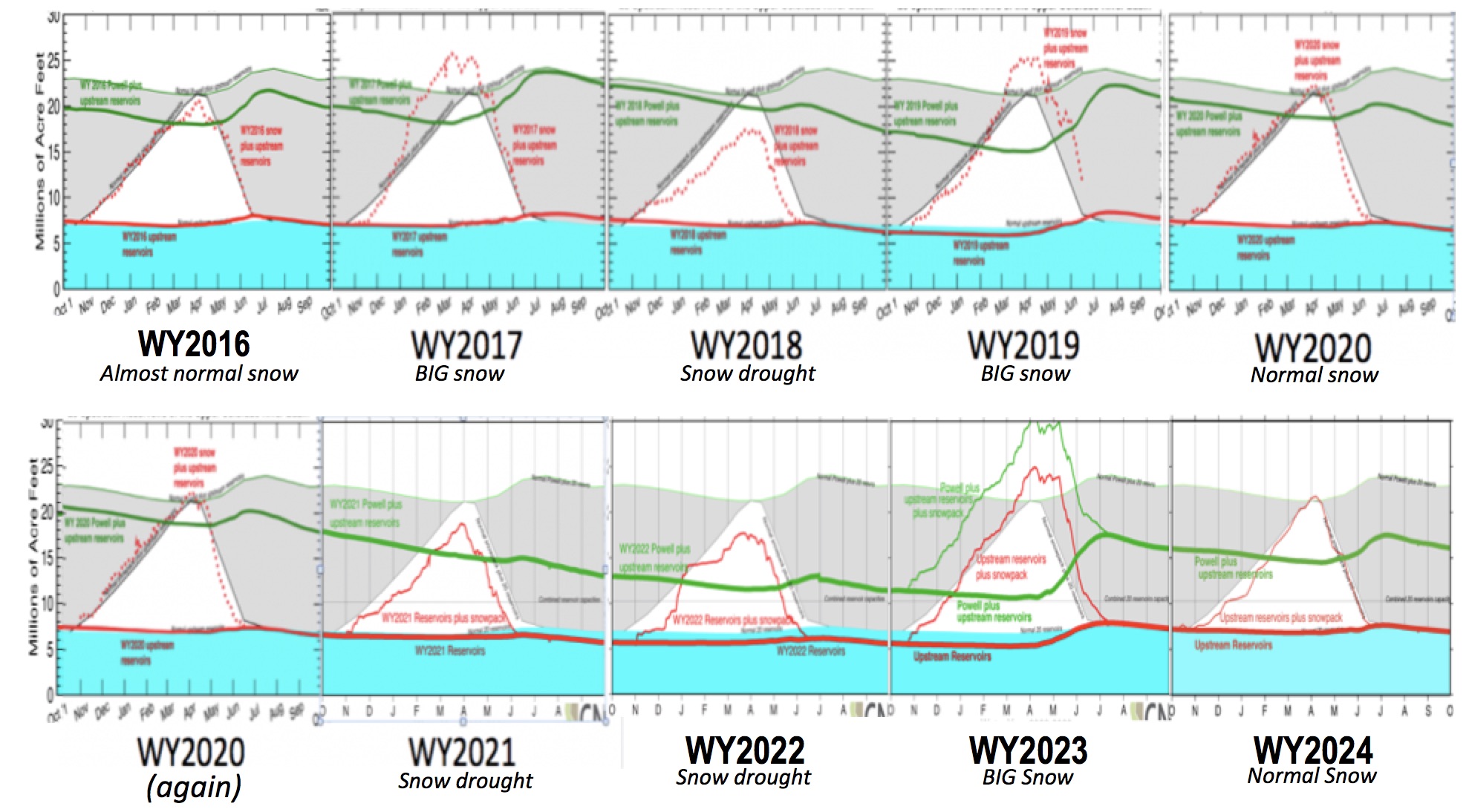

The following figure is a composite of the bottom frames of those UCRB storage figures for water years 2016-2024. Taken together, the long-term decline in reservoir storages is pretty clear, albeit with occasional rebounds in wet years.

Notice in this composite figure that:

- A single BIG-snow year (e.g., 2017, 2019 & 2023) can dramatically reverse longer term storage declines, but only briefly.

- Isolated near-normal snow years (e.g., 2016 & 2024) hold their own but do not undo previous storage declines; notably, 2020 was a near-normal snow year that did not even prevent further storage loss.

- Dry years in 2018, 2021 & 2022 led to ~5 MAF declines in upstream-reservoirs-plus-Powell storages.